by: Mal Vickers

Imagine you’re in the midst of the stress of VCE and facing those life-changing questions: What do I do with my life? Which university course should I do? You’d want accurate and reliable information, right?

Sadly I witnessed an audience of impressionable, aspiring young people who were considering career moves being given poor information by an Australian university.

In August 2015, I sat in on RMIT’s Open Day presentations promoting a degree courses in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). By the look of the demographic in attendance, most were Year 12 students. About one quarter looked to be the parents, with a few possible mature-age students and one known skeptic, MOI.

Young people are going to be exposed to misleading information and dubious advertising in society, that’s a given. As a society, we’re already taking up a lot of valuable educational time in teaching science and critical thinking, but class time is limited. How much time should we devote to educating students about the many ways people can be misled?

I don’t think we can expect Year 12 students to understand the boundaries of research in alternative medicine. Most mature adults don’t have a good grasp of the science behind alt-med. In my humble opinion, a university has the responsibility to tell potential students honestly about what they’re considering getting into when they attend an Open Day presentation. If the science is dubious, then tell potential students that and tell them in unambiguous terms.

RMIT promotes a number of degree courses in traditional and alternative medicines: chiropractic, osteopathy, myotherapy and traditional chinese medicine (TCM). TCM is split into two main streams, herbal and acupuncture.

Here’s a snippet from RMIT’s 2015 Open Day. The presentation was about TCM. The presenter was discussing herbal treatments:

So what can we [Chinese herbal medicine] treat? Chinese medicine can be used to treat various conditions. We use it for insomnia or we can use it for common cold. We have a lot of patients with common cold and they have asthma. Particularly for the chronic asthma, because acute condition already helped a lot in emergency. So we see number of patients with the chronic asthma. And we can use herbal medicine for digestion problems. So we can use it for like bloating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, IBS, so irritable bowel syndrome. And also we can use it for a lot of mental problems. We see some patients that have got anxiety, depression. So these herbs [pointing] are for these conditions as well. And these days, because of the work, postures, the working environment, a lot of people experience pain, headache, the joint pain, arthritis, a lot of pain conditions herbal medicine can help as well.

And while discussing Chinese medicine herbal creams for skin conditions, the same presenter said:

So we also use it for skin conditions. For young people we see the pimples, acne. So we mix some cream, the herbal cream, to help your pimples.

Time to apply that old skeptical mantra – extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. I thought these claims were somewhat dubious, so I decided to investigate.

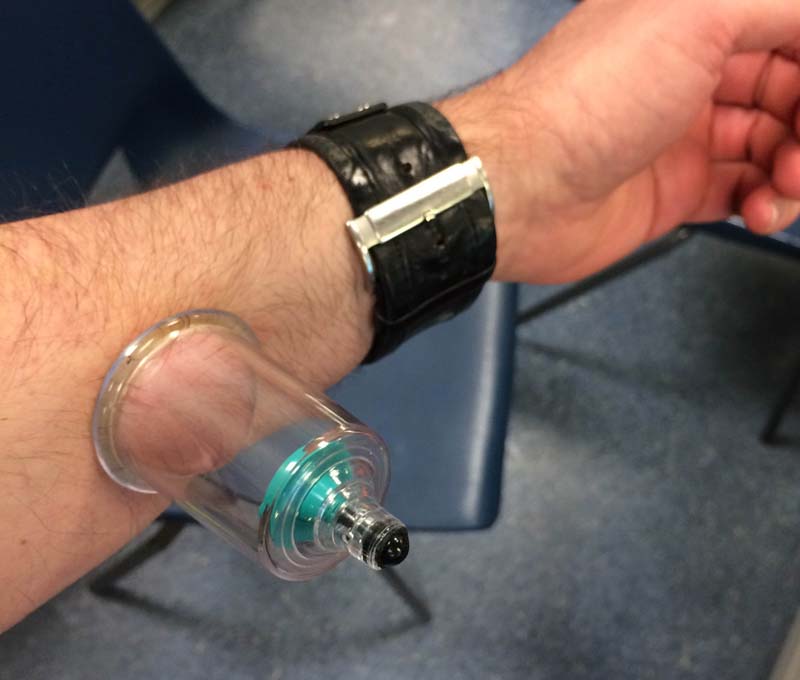

Because the claims above were made in the context of traditional Chinese herbal medicine, that’s where I concentrate my attention. However, readers should understand that TCM incorporates a bewildering array of techniques and ideas, such as massage, yin-yang, cupping, qi, meridians, acupuncture, moxibustion etc.

I wrote to RMIT’s TCM people about the claims to treat various health conditions with herbs. The response was quite underwhelming; they sent me guidelines for clinical practice, nothing that referenced the scientific medical literature – not very useful.

To be fair to RMIT, I’ll try to check these claims for myself; perhaps there is something in these claims but somehow I’ve missed it. In modern internet times, medical research is a lot easier than it once was. However, as we know, there’s a lot of nonsense out there. I’m going to take a careful and responsible scientific approach when checking RMIT’s claims.

However, I’m not going to put detailed medical research into the middle of this blog post – it would instantly stop being a readable blog post at that point. Just give me the bottom line I hear you say. Sure, here it is:

The above claims that herbal traditional Chinese medicine can effectively treat the health conditions mentioned lacks scientific credibility. The students and others who attended this presentation were poorly informed.

There you have it.

I still must try diligently to verify the claims made by RMIT, lest I be accused of not knowing my stuff. I’ve put the research for each health condition in Appendix A (below), listing all the treatment claims made by RMIT in the quote above.

I guess most readers know what a clinical trial is – you might have participated in one or have a friend or family member who has. It’s the best way to find out whether a potential new medicine is effective or not. When we dig into the scientific medical literature, we find the published results of millions of clinical trials. Having some idea of how to sort the wheat from the chaff is essential to making sense of it all.

There’s another form of scientific publication that might get an answer for us much faster – the systematic review. Systematic reviews critically analyse the evidence from many clinical trials in order to come to an overall idea about a particular scientific question.

Here is the conclusion from a review that put together the results of other systematic reviews of traditional Chinese medicine:

Most Cochrane systematic reviews of TCM are inconclusive, due specifically to the poor methodology and heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. Some systematic reviews provide preliminary evidence of Chinese medicine’s benefits to certain patient populations, underscoring the importance and appropriateness of further research. These preliminary findings should be considered tentative and need to be confirmed with rigorous randomized controlled trials. [1]

For those who haven’t followed this conclusion: it’s not good for TCM. I’ll put it into plain English. Summing up the scientific literature as a whole in relation to TCM and broadly describing why there’s a problem, the “rigorous randomized controlled trials” needed to confirm the many claims of TCM just don’t exist in the scientific literature.

Regardless of my own research (see below), the above conclusion is enough to indicate there’s a problem with the claims made during Open Day at RMIT.

These claims were quite specific:

We use it [herbal TCM] for insomnia … common cold … asthma … digestion problems … bloating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea … irritable bowel syndrome … mental problems.

They “use it” for these health conditions on real patients at RMIT’s TCM teaching clinic. The impression given is that the science must be settled, right? No, it’s not, not according to the conclusion of the good-quality review I mention above.

Not all readers may be aware of what goes on in medical research. Rigorously conducted clinical trials involve a small group of highly trained people doing coordinated work, studying lots of patients over a significant period of time. It’s expensive and it’s time consuming. Real medical researchers don’t take the alt-meds like TCM very seriously; they look implausible and rely on magic thinking, so why waste valuable research dollars on them? For that reason, most investigations of alternative medicines such as TCM are done by people who already believe in them and are practitioners or lecturers in e.g. TCM. They don’t like to use the tough and difficult “rigorous randomized controlled trials” as a starting point. Perhaps this is because rigorous trials tend to produce negative results and negative results tend not to get published. As such, the research into TCM is a bit of a shambles. Typically we find poorly conducted trials with the door wide open to the personal biases of the investigators.

Here’s another review of TCM that states the problem very clearly:

Biases are present both in placebo-controlled trials of CHM [Chinese herbal medicine] and conventional medicine, but may be most pronounced in CHM trials published in Chinese-language journals. [2]

That’s a very blunt assessment; I’m not sure I’d say it that way. I suggest this finding is more about pre-existing belief in the treatment and the country in which that pre-existing belief is most predominant.

Professor Edzard Ernst also has an excellent blog post describing why TCM research is not good science.

When we wade through the literature on TCM, as I’ve done (see Appendix A), one of the most obvious problems with the TCM medical research literature is the lack of placebo control. When testing herbal preparations, making a suitable placebo isn’t difficult. You put a relatively neutral substance – ground rice for example – into gelatine capsules instead of the TCM herb under test.

Another problem with TCM herbal clinical trials is the lack of analysis of the product under test. We see in my research below that some of the trials of TCM I found show positive results. However, this information should be looked at in context; a recently released Australian study said:

In 50% of the TCMs, an undeclared pharmaceutical agent was detected including warfarin, dexamethasone, diclofenac, cyproheptadine and paracetamol.

And:

The study showed 92% of the TCMs examined were found to have some form of contamination and/or substitution. [3]

This alarming finding needs to be assessed alongside the small number of positive trials found in my search of the literature (Appendix A). It puts anyone trying to investigate the efficacy of TCM herbal mixtures in a difficult position. Is it the TCM herbs that are producing any beneficial health effect, or does the beneficial effect come from undeclared pharmaceuticals?

I couldn’t find any positive studies where the researchers had gone to a lot of trouble to make sure there was no contamination (substitution or pharmaceuticals) of the herb under test.

Let’s look at what else was said at RMIT’s 2015 Open Day:

The first couple of years you will learn the basic knowledge of medicine and then you will learn the Chinese medicine theory. Chinese medicine theory is quite different because it was inherited from the Chinese ancient philosophy, so it has some special theory inside. Maybe for student at the beginning when you first heard of that you might get a bit confused, but later, once you put everything together, you might find it’s very interesting.

So according to the presenter, the reason that students get confused by Chinese medicine is that they must unlearn what they have learnt in their previous years of regular schooling. For instance, did you know that in TCM, food is thought to travel from the stomach to the spleen and then on to the small intestine?

Does that make your head spin? Like me, are you thinking: but wait! What? Modern anatomy is based on solid observational evidence gathered through performing detailed dissections. The stomach is situated just above the small intestine and the two are connected by a tube-like structure known as the duodenum.

TCM practitioners don’t believe this, however. But why would food, in the process of being digested, travel from the stomach to the spleen (which is to the left side of the stomach and not part of the gastrointestinal tract) then purportedly go down and do a sharp right turn to the small intestine? That’s correct: food undergoing digestion doesn’t travel this way, but TCM practitioners are taught the stomach–spleen–small intestine path in the TCM paradigm.

(The spleen, for readers who may not know, in reality helps with filtration of the blood and with red blood cell storage and production. It’s a very well-studied organ in medical science.)

I don’t know what happens if someone has a medical problem associated with their duodenum and visits a TCM practitioner – that would be an interesting experiment, volunteers, anyone?

Something else I find troubling about TCM is that it doesn’t include a modern understanding of the nervous system. As far as I can tell, TCM is based on a kind of fictional anatomy; it’s like a religious belief.

To help make more sense of this, I should also explain that in ancient China dissection was considered immoral. Chinese medicine had strict ethical guidelines that prevented human dissection – as such, they were just guessing. The history of TCM includes the well-known ancient Chinese philosopher Kong Qiu, better known in the West as Confucius, along with many other highly revered people. It’s considered disrespectful, perhaps even blasphemous, to question the founders of TCM.

Religious ideas about the human body are not easily refuted. Heavily influenced by the Judeo-Christian beliefs of his time, Dr Duncan MacDougall (US) in 1901 tried to weigh the human soul. (He succeeded of course.) The silliness of trying to weigh a soul should be kept in mind as we try to give some perspective to the religious ideas in TCM anatomy.

Confucius was by all accounts a great and wise philosopher; he taught a great deal about ethics, manners, treating people kindly, helping people, respect for others including the sick and dying, and admiring one’s ancestors. Confucian medical ethics were ahead of their time. Confucius knew that for medical practitioners it’s wrong to gain material advantage from those who are unfortunately unwell or dying. We’re still troubled by ethical questions like this today – how much should we charge a patient for life-saving surgery or drugs?

I see these issues as quite distinct. If you’re a medical practitioner, medical ethics can tell you how to relate to people who are unwell; don’t rip them off, for example. However, modern medical science with its controlled trials is the best guide for determining which treatment to apply for particular health conditions.

While science relies on rigorously testing, questioning, debating the evidence and throwing away what doesn’t work, that’s not the way of belief and dogma. That’s why, to me, TCM looks more like a religion and less like a science. TCM has the immunity to criticism common to belief systems. Its belief system may include good ethics, but that shouldn’t be used to paper over the associated dubious ideas: hot and cold treatments, qi, meridians, acupuncture, moxibustion and cupping. I’m clearly some kind of TCM heretic.

The RMIT presenter was right in saying that confusion will inevitably develop in the minds of TCM students; this confusion must be profound. But when you’re a student, you participate in the process to get ahead. You try to write the things you think examiners will like, so that you’ll pass your exams. Dealing with mutually incompatible systems (in this case TCM versus modern medicine) is left up to the student.

I find it bizarre that TCM is taught at degree level in an Australian university and is sanctioned by government regulators like AHPRA. Why learn something that’s medical fiction? How could this possibly be helpful to anyone with a serious medical condition?

RMIT is quite open about the pseudoscientific nature of TCM. See this promotional video.

Transcript at 57 seconds:

Let’s imagine in the body there are meridians. And in these meridians we have qi flow, we have energy flow.

I don’t see why we need to imagine meridians in our bodies? I’ve got an alternative imaginary experiment – let’s instead imagine using Occam’s Razor, let’s throw away meridians as an unnecessary idea.

The video also tries to link meridians with “energy” – equally nonsensical.

A discussion of TCM wouldn’t be complete or fair without mention of artemisinin (pronounced ar-te-MEYE-sin-in), also known as qinghao su. Artemisinin is a very useful drug that, in compounds, is used to treat a common type of malaria. It’s quite an amazing recent discovery and there’s no question that it’s saved many thousands of lives. I won’t take this post on a tangent; you can read the full details at these links, here and here.

The discovery of artemisinin highlights the difference between something that is measurably effective, and the bulk of TCM herbal preparations in the impressive shelves and cabinets that line your local TCM practitioner’s store – they don’t have the evidence behind them that artemisinin does.

Artemisinin was isolated from thousands of other TCM herbal remedies, real science was done and a Nobel prize was awarded. So one chemical derived from one TCM herb has efficacy (in a compound) for one type of the tropical disease malaria; on that basis, is it reasonable for RMIT to train TCM practitioners to set up shop in chilly-wet, mid-latitude Melbourne?

The isolation of one effective compound from many thousands doesn’t validate the whole of TCM; it only shows that the science should be done ahead of the marketing.

Returning for a moment to the transcript from RMIT Open Day, we note that malaria was not one of the health conditions mentioned.

Readers should also note that I requested an interview with an RMIT representative of the TCM course before Open Day. After I supplied questions representative of those I might ask in the interview, my request was declined.

China is a country of contradictions; anyone who’s been there will tell you so. Of course I understand that China is a technologically advanced country which has a well-funded medical research program and a successful space program. This doesn’t explain why we need to lower the bar for what in Australia we consider to be evidence-based medicine.

My challenge to RMIT: be completely honest to potential students during Open Day – it’s what Confucius would want you to do.

References

-

Manheimer E et al., Evidence from the Cochrane collaboration for traditional Chinese medicine therapies. J Altern Complement Med. 2009 Sep;15(9):1001–14. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0414.

-

Shang A et al., Placebo-controlled trials of Chinese herbal medicine and conventional medicine – a comparative study. International Journal of Epidemiology, V36, I5, p1086–92.

-

Coghlan ML et al., Combined DNA, toxicological and heavy metal analyses provides an auditing toolkit to improve pharmacovigilance of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Sci Rep. 2015 Dec 10;5:17475. doi: 10.1038/srep17475.

Appendix A

The specific health conditions claimed by an RMIT representative at Open Day 2015 to be treatable with herbal TCM are listed in the headings below. A large online database of peer-reviewed medical literature, PubMed, was searched to look for relevant and rigorously conducted clinical trials and systematic reviews.

In assessing trials for quality:

- Patient blinding, to remove bias via the placebo effect, is a very important control when assessing studies. Blinding can easily be achieved by encasing the real TCM herb (the active ingredient) in a gelatine pill case compared with an irrelevant substance (the placebo ingredient). As such, the treatment experience of those taking either the active or the control i.e. swallowing a capsule, would be identical.

- In checking the quality of controlled trials, it’s also important that those assessing the patients were not aware of which treatment the patient was on, real versus placebo. This is called “assessor blinding” and is another way that bias can be removed from a trial.

- There are many other factors that should be assessed in order to rate the quality of a trial. How many patients? How well were the patients randomised to the groups? Were those involved in conducting the trial independent of any prior beliefs about the treatment and outcomes? Was the trial registered?

- Of particular importance to trials of TCM herbal treatments: How sure can we be that the named herb under test wasn’t contaminated? This is a very significant and known problem [3].

Insomnia

Search URL used to find evidence in relation to TCM and insomnia.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+medicine+Insomnia

The above search yielded 218 results; notable studies found are discussed below:

*

Ye Q et al., Efficacy of zhenjingdingzhi decoction in treating insomnia with Qi-deficiency of heart and gallbladder: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. J Tradit Chin Med. 2015 Aug;35(4):381–8. PubMed Abstract

Discussion:

No placebo control. The trial uses the unsupported idea of “qi deficiency” in the selection criteria – high risk of bias.

*

Chan YY et al., Clinical efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine, suan zao ren tang, for sleep disturbance during methadone maintenance: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:710895. doi: 10.1155/2015/710895. Epub 2015 Aug 4. PubMed Abstract

Discussion:

About insomnia during methadone treatment – not relevant to the wider population.

*

Yeung WF et al., Prescription of Chinese herbal medicine and selection of acupoints in pattern-based traditional Chinese medicine treatment for insomnia: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:902578. doi: 10.1155/2012/902578. Epub 2012 Nov 28. PubMed Abstract

Discussion:

A review with inconsistent results.

Nothing else of significance was found in the “insomnia” search. The result of the search was also checked for any good-quality systematic reviews – none were found.

Common cold

Search URL used to find evidence in relation to TCM and the common cold.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+medicine+common+cold

The above search yielded 105 results; notable studies found are discussed below:

Min J et al., Efficacy and safety of gantong granules in the treatment of common cold with wind-heat syndrome: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015 May 19;16:219. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0735-9. PubMed Abstract

Discussion:

The abstract indicates that the trial has been registered but not completed, so no conclusions are available.

*

Chen W et al., Chinese proprietary herbal medicine listed in ‘China national essential drug list’ for common cold: a systematic literature review. PLoS One. 2014 Oct 20;9(10):e110560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110560. eCollection 2014. PubMed Abstract

Discussion:

This is a systematic review looking at “Chinese proprietary herbal medicine” (CPHM) and the common cold. The conclusion is negative: “is not supported by robust evidence.”

*

Chang J et al., Treatment of common cold patients with the shi-cha capsule: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:254571. doi: 10.1155/2012/254571. Epub 2012 Dec 27. PubMed Abstract

Discussion:

Inconclusive result: “not statistically significant.”

*

Search for Traditional Chinese Medicine and Rhinovirus.

Note: The above search using “common cold” in the search terms produced many non-specific results. The search term “rhinovirus” was used instead to try to find more relevant results.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+medicine+rhinovirus

Yamaya M et al., Hochu-ekki-to inhibits rhinovirus infection in human tracheal epithelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2007 Mar;150(6):702–10. Epub 2007 Feb 19. PubMed Abstract

Discussion:

Not a clinical trial.

Asthma

Search URL used to find evidence in relation to TCM herbal and asthma.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+medicine+asthma

The above search yielded more than 400 results.

For the sake of brevity and quality, the results of the following relevant systematic review are discussed. It should be noted that this study covers all herbal treatments, not only herbal TCM.

Arnold E et al., Herbal interventions for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD005989. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005989.pub2. [full text]

Conclusion:

On the basis of the evidence presented in this review, the authors conclude that although some herbal preparations have shown improvement in subjective measures of asthma symptoms, this is not strongly supported by objective measures, and may be related to biases within the studies such as inadequate blinding.

Digestion problems

This term is too vague to produce meaningful results when searching the medical literature.

Bloating

Bloating is associated with irritable bowel syndrome (see below).

Search URL used to find evidence in relation to TCM and bloating.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+medicine+bloating

Discussion:

15 results – no placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Nausea/vomiting

Note: Searching the medical literature for “nausea” alone produced very similar results to searches for “vomiting” alone. As such, the results for both are discussed below.

Note: Similar results were found when substituting the search term “emesis” (the medical term for vomiting).

The medical literature was searched for systematic reviews of TCM and both “nausea” and “vomiting”. Result: No relevant and good-quality systematic reviews could be found that assess the efficacy of herbal TCM in the treatment or prevention of nausea and vomiting.

Search URL used to find individual trials related to TCM and nausea.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+medicine+Nausea

Search URL used to find individual trials related to TCM and vomiting.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+medicine+vomiting

Notable studies found in the above search are discussed below:

Xu L et al., Jian pi li qi decoction alleviated postembolization syndrome following transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015 Nov 20. pii: 1534735415617020.

Discussion:

The conclusion discusses only liver function – not relevant.

*

Chan KK et al., The use of Chinese herbal medicine to improve quality of life in women undergoing chemotherapy for ovarian cancer: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial with immunological monitoring. Ann Oncol. 2011 Oct;22(10):2241–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq749. Epub 2011 Feb 25.

Discussion:

Specifically about patients dealing with the symptoms of chemotherapy. Negative result: quality of life was not improved.

*

Mok TS et al., A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study of Chinese herbal medicine as complementary therapy for reduction of chemotherapy-induced toxicity. Ann Oncol. 2007 Apr;18(4):768–74. Epub 2007 Jan 17.

Discussion:

Specifically about patients dealing with “chemotherapy-induced toxicity”, therefore the trial is not necessarily relevant to nausea sufferers in the wider population. The study looked for a number of possible positive outcomes. “Grade 2 nausea” was reduced. It’s unclear from the research abstract whether the “combination of single-item packaged herbal extract granules” was assessed for contaminants.

*

Sun DZ et al.,Therapeutic effect of jinlongshe granule on quality of life of stage IV gastric cancer patients using EORTC QLQ-C30: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Chin J Integr Med. 2015 Aug;21(8):579–86. doi: 10.1007/s11655-014-1950-z. Epub 2014 Nov 16.

Discussion:

Specifically studied gastric cancer patients and assessed one TCM ingredient only. Both control and active groups received herbal TCM.

Diarrhoea

Search URL used to find evidence in relation to TCM and diarrhoea.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+medicine+diarrhoea

The resulting trials found in this search were almost the same as the trials found for irritable bowel syndrome. Please refer to the assessment immediately below.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

One systematic review was found which assessed the use of TCM herbal treatments for IBS.

Shi J et al., Effectiveness and safety of herbal medicines in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Jan 21;14(3):454–62.

Discussion:

The review authors found 22 studies which met the inclusion criteria for this review. Most of these studies were rejected because they were of poor quality; only 4 studies were retained for inclusion in the review. Although most studies were excluded, those studies which were included were not assessed for their level of patient blinding to the treatment: “irrespective of blinding”.

The conclusion of this review is positive:

Herbal medicines have therapeutic benefit in IBS.

However, there is a high risk that the conclusion of this review is biased due to the inclusion of unblinded trials in the review. It’s also possible that the trials included in this review used TCM remedies which were not assessed for contaminants such as real pharmaceuticals.

*

Search URL used to find evidence in relation to TCM and IBS.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+irritable+bowel+syndrome

Notable studies found in the above search are discussed below:

Xiao Y et al., The efficacy of shugan jianpi zhixie therapy for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 8;10(4):e0122397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122397. eCollection 2015

Discussion:

Systematic review of one TCM herbal mixture (the details of the mixture are not made clear in this paper: “an ancient formula”). The conclusion makes a positive statement about shugan jianpi zhixie therapy:

suggests that SJZT is an effective and safe therapy option for patients with IBS-D.

However, the authors also appreciated the high variability and low patient numbers of the studies they referenced and on which this conclusion relies:

However, due to the high clinical heterogeneity and small sample size of the included trials, further standardized preparation, large-scale and rigorously designed trials are needed.

*

Zang SS et al., A multi-center randomized controlled trial on treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome by Chinese medicine syndrome-differentiation therapy [translated from Chinese], Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. [Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine] 2010 Jan;30(1):9–12.

Discussion:

High risk of bias; in the Aims section, the authors suggest they already have a conclusion in mind and are trying to verify it:

To verify the clinical efficacy of Chinese Medicine syndrome-differentiation therapy.

Also, this trial is single-blinded, not double-blinded. The actual TCM treatment used is not made clear in the abstract (it may not have been TCM herbal, in which case it would not be relevant to this investigation).

*

Liang ZF et al., Tiaohe ganpi hexin decoction in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: a randomized controlled trial [translated from Chinese], Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. [Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine] 2009 Sep;7(9):819–22. doi: 10.3736/jcim20090904.

Discussion:

The trial patients were not blinded to the treatment they received. The trial was very small: 20 treatment patients, 20 control patients.

*

Gao WY el al., Effects of changjishu soft elastic capsule in treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel patients with liver-qi stagnation and spleen deficiency syndrome: a randomized double-blinded controlled trial [translated from Chinese], Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. [Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine] 2009 Mar;7(3):212–17.

Discussion: High risk of bias. The patients were assessed for suitability for participation in the trial using the unverified idea of “qi” and from a TCM interpretation of symptoms:

Chinese herbal medicine for smoothing liver, invigorating spleen and regulating qi activity, on diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (D-IBS) patients with liver-qi stagnation and spleen deficiency syndrome.

The researchers did not analyse the changjishu soft elastic capsule for the presence or absence of pharmaceuticals.

*

Leung WK et al., Treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome with traditional Chinese herbal medicine: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Jul;101(7):1574–80.

Discussion:

The result was negative: “The use of this herbal formulation for diarrhea-predominant IBS did not lead to global symptom improvement.”

Anxiety

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=traditional+chinese+medicine+anxiety

This search yielded 334 results; one study of interest found:

Park DM et al., The comparative clinical study of efficacy of gamisoyo-san (jiaweixiaoyaosan) on generalized anxiety disorder according to differently manufactured preparations: multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014 Dec 2;158 Pt A:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.024. Epub 2014 Oct 23.

Discussion:

For anxiety patients, the conclusion is negative: “Gamisoyo-San did not improve anxiety level of GAD patients.”

*

Depression

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Traditional+Chinese+medicine+depression

The above search yielded 750 results.

For the sake of brevity and due to the large number of results found in the literature search, I rely on the results of the following two systematic reviews:

Weung WF et al., Prescription of Chinese herbal medicine in pattern-based traditional Chinese medicine treatment for depression: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:160189. doi: 10.1155/2015/160189. Epub 2015 Jun 9.

Discussion:

The review finding is inconclusive:

Due to the limited number of studies on TCM pattern-based treatment of depression and their low methodological quality, we are unable to draw any conclusion regarding which herbal formulas have higher efficacy and which TCM patterns respond better to CHM [Chinese Herbal Medicine].

*

Weung WF et al., A systematic review on the efficacy, safety and types of Chinese herbal medicine for depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2014 Oct;57:165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.05.016. Epub 2014 Jun 12.

Discussion:

The review finding is inconclusive:

Despite the overall positive results, due to the small number of studies with sufficient methodological quality, it is premature to accurately conclude the benefits and risks of CHM for depression.

Headache

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Traditional+Chinese+medicine+Headache

The above search yielded 186 results.

Yu S et al., A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of duliang soft capsule in patients with chronic daily headache. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:694061. doi: 10.1155/2015/694061. Epub 2015 May 26.

Discussion:

No assessment of what was in the capsules under test. The result is inconclusive: “However, no statistical difference was found between the two groups in the associated symptoms.”

*

Xiao Y et al., Traditional Chinese patent medicine for prophylactic treatment of migraine: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Eur J Neurol. 2015 Feb;22(2):361–8. doi: 10.1111/ene.12581. Epub 2014 Oct 25.

Discussion:

The reference to “patent medicine” indicates that the researchers did not know the ingredients of the medicine. The positive result may be due to the pharmacology of the medicines under test.

Joint pain

Search used to find the evidence in relation to TCM and joint pain.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Traditional+Chinese+medicine+joint+pain

The above search yielded 206 results. Relevant studies found in the above search are discussed below.

Hou PW et al., Traditional Chinese medicine in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015 Jul 2;5(4):182-96. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2015.06.002. eCollection 2015.

Discussion:

A systematic review, the outcome was quite conclusive for TCM herbal:

…no evidence was found regarding the effects of herbal medicine on pain or physical function.

*

Lechner M et al., Efficacy of individualized Chinese herbal medication in osteoarthrosis of hip and knee: a double-blind, randomized-controlled clinical study. J Altern Complement Med. 2011 Jun;17(6):539-47. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0602.

Discussion:

Not fully placebo controlled – still negative.

While the individual prescription consisting of medicinal herbs according to TCM diagnosis investigated in this trial tend to improve the osteoarthritis, the same effect was also achieved with the nonspecific prescription.

Arthritis

Search used to find the evidence in relation to TCM and arthritis:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Traditional+Chinese+medicine+arthritis

The above search yielded 952 results. Note, all of the papers found in the “joint pain” section above were also found in this search and should also be considered in this section.

For the sake of brevity, noting the large number of results found in the above search a further two searches were done to find (1) only systematic reviews and (2) only placebo controlled clinical trials relating to TCM and arthritis research.

Search used to find relevant systematic reviews.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Traditional+Chinese+medicine+arthritis+systematic

This search yields 50 results. Two relevant systematic review were found in the search results:

Zhang W et al., Evidence of Chinese herbal medicine Duhuo Jisheng decoction for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. BMJ Open. 2016 Jan 4;6(1):e008973. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008973.

Discussion:

Duhuo Jisheng is a commercially available TCM herbal mixture, available in pill form. It is commonly prescribed for arthritis by TCM practitioners. The result of the review was inconclusive:

…the effectiveness and safety of DJD is uncertain because of the limited number of trials and low methodological quality. Therefore, practitioners should be cautious when applying DJD in daily practice. Future clinical trials should be well designed; more research is needed.

*

Liu Y, et al, Extracts of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:410793. doi: 10.1155/2013/410793. Epub 2013 Dec 4.

Discussion:

The outcome was inconclusive:

However, the efficacy of TEs in treating RA should be further estimated with better designed, fully powered, confirmatory RCTs that apply the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) improvement criteria to evaluate their outcomes.

Search used to find relevant placebo controlled clinical trials.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Traditional+Chinese+medicine+arthritis+placebo+clinical

This search yielded 21 results. No high quality, rigorous, placebo controlled clinical trials were found.

Acne

Search used to find the evidence in relation to TCM and acne:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Traditional+Chinese+medicine+acne

The above search yielded 53 results.

Note that the claim made at RMIT Open Day 2015 was for positive results with a TCM skin cream. Of the 53 results found in the above search, only the trials that use TCM skin creams as the active treatment will be selected for consideration. No placebo controlled clinical trials using a TCM skin cream to treat acne were found in the results of the above search.

Reblogged this on The Logical Place.